Annex: Technology-specific risks for renewable energy technologies

(Accompanying paper: Is “technology neutrality” appropriate to sustain renewables deployment?)

Deep geothermal technology

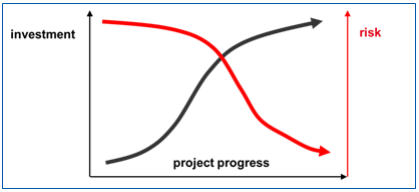

Most of the investment falls into the initial, high-risk phase of a geothermal project. While the project is being developed, the required budget changes successively. And with increasing effort in exploration, more and more knowledge about the resource is acquired and the risk of failure decreases accordingly’.

Fig.: Risk and cumulative investment during the project progress. Source GEOELEC final report [p. 50].

The bottleneck of many geothermal projects is that in most cases debt financing by banks is possible only following the completion of the long-term flow tests. Furthermore, due to the limited practical geological knowledge in some regions, private insurers consider the operation to be too risky. Under those conditions, tailor-made instruments (including some form of risk insurance) are crucial for the successful financing of a project.

Ocean energy technologies

Ocean energy projects are considered risky for investors because, until enough operating hours in real sea conditions have been clocked up by the device, its manufacturer (Original Equipment Manufacturer or OEM) is not in a position to offer a performance guarantee to the buyer (project developer, power producer, utility). The buyer will be willing to take some of the project risk, as investing in maturing technologies is a strategic option, but will be reluctant to take the entire risk linked to device underperformance. There is, therefore, a gap between the performance that the OEM will guarantee and the amount of under-performance risk the project developer is willing to take.

A production support mechanism (such as a feed-in tariff, feed-in premium, etc.) is necessary for the project developer to make a solid business plan. However, it will not be enough to eliminate the risk of device under-performance, as that will affect production and, therefore, income.

Some up-front support is therefore required. Also, financial instruments such as a publicly under-written fund to insure the difference between estimated device performance and real performance would reduce risk perception for investors. Such private insurance products exist for mature technologies. However, due to the production risk in ocean technologies such products are not available or are prohibitive. Consequently, publicly under-writing of the insurance product is required

Offshore wind

Offshore wind has grown to 11GW as of January 2016 up from only 1GW in 2007. The cost of deployment has reduced by 25.3% and industry is on course to deliver on self-imposed targets to increase competitiveness of the sector (€100/MWh by 2020).

The scale of developments and investment needed to put up an offshore wind farm calls for unique considerations that may not apply for onshore wind or other renewable energy technologies.

In particular, the deployment of offshore wind in the EU would require a regional cooperation model to clarify the timing and sizing of tenders, which would establish the market visibility and stability that is key to high capital investment. Additional cooperation on grid development, regulatory frameworks alignment and identification of joint projects could also further enhance project economics and accelerate the trajectory of offshore wind to full cost competitiveness.

Technology-specific tenders are best suited for offshore wind in order to maintain investments needed and technological development resulting in further cost reduction potential.

Concentrated solar power (CSP)

Many of the risks associated with building a CSP project are market and site-specific and are accompanied by a number of common logistical, construction and operational risks, including:

- Transit risk: there is a substantial logistical challenge involved in transporting parts and equipment to remote project sites. Transporting key components across long distances, often overseas, can result in equipment getting damaged, broken, or misplaced in transit. Furthermore, if equipment is mishandled, or damages occur during the loading or unloading stages, this can have a wide-ranging impact on the project as a whole, as developers are forced to wait for repairs to be completed, or replacement parts brought in. Employing experienced transportation contractors, and adhering to route surveys can minimize the risks involved at this stage of a project.

- Construction risk: Since CSP is a relatively new technology, and not yet widely deployed, lack of contractor experience can prove an issue and may lead to project delays in the short-term, and, in the long term, site performance issues. To ensure a CSP plant is put together correctly, in such a way as to optimize its output, contractors with a proven track record, and solid understanding of the region, should be employed to handle the construction of a project.

- Geographical risk: Depending on the location of a plant, weather phenomena can also undermine its production levels. Desert flash floods are not uncommon, and these, more than flood plains or river flooding, pose the greatest risk to CSP plants, which are invariably located in desert regions. In such regions, projects can also be susceptible to windstorms, tornados, cyclones, hurricanes and dust storms. Drainage systems, flood canals, dykes and water pumps can be used to minimize the risk of water damage, and the automatic stowing of mirrors can help protect plants from the risk of strong winds. As CSP looks to become a viable, investment grade generation form, protecting sites against the market-specific and technological risks outlined above will be crucial to the success of the emerging industry.

Solar thermal technology

The main risks for project development in the solar thermal field relates to long term performance predictability, stemming from potential damages to the system (extreme weather, inadequate maintenance) and performance degradation. Although performance predictability is in most cases extremely accurate for the first years of functioning of a solar thermal collector, accuracy tends to

dwindle over the lifetime of the system, which commonly exceeds 20 years. This lack of long-term exact predictability is somewhat deterrent for large investors, or even ESCOs who need specific performance assurance over the full economic and/or technical lifetime of the project.

System and performance degradation can also come as the result of problems in the installation phase. Without proper maintenance and monitoring, such problems can affect performance over the long term. Therefore, any technology specific support in this case, should include tailor-made flanking measures targeting for instance installers’ certification and training and promoting metering and monitoring solutions.

Solar PV technologies

Investors in large and in small PV plants have substantially different profiles. Small investors have much lower capital availability and critical mass than big investors; hence, multi-step, competitive procedures for project support are not appropriate for them. Yet, both large and small plants make sense from a system perspective; hence, tailor-made support is needed.

Heat pump technologies

In the current market framework, investment cost (CAPEX) for heat pumps are still higher than those for incumbent technologies. Short term decision making horizons favor investment in fossil boilers. Consequently the respective emission characteristics are fixed for the next 15-20 years.

Operating cost are typically lower for heat pumps than for incumbent technologies. Governments should keep cross-sector effect in mind when designing support mechanisms. Most detrimental for heat pumps is the design of a repayment mechanism for feed-in tariffs via a levy on electricity prices. While the greening of electricity production is achieved, rising electricity prices increase the operating cost for electric compression heat pumps. This approach provides an additional advantage on the use of fossil energy and inhibits a faster connection of the electricity and thermal energy sectors.

Support mechanisms should help overcome the first cost investment disadvantage. They should take cross-sector effects into considerations. Feed-in tariffs should not be refinanced by a levy on one energy source (in the heat pump case: electricity) alone, but should be spread over all energy use.

The signatories: